Eric Kronberg, a respected urbanist architect and developer in Atlanta, leads Kronberg Urbanist + Architects (Kronberg U+A), alongside Elizabeth Williams and their talented team. More than just designers, they are influential advocates for smart, sustainable development. They perpetually crank out insightful graphics—like the one above—that help illustrate key urban planning concepts. (Stay tuned for more OnHousing posts that build on their work as a launching point).

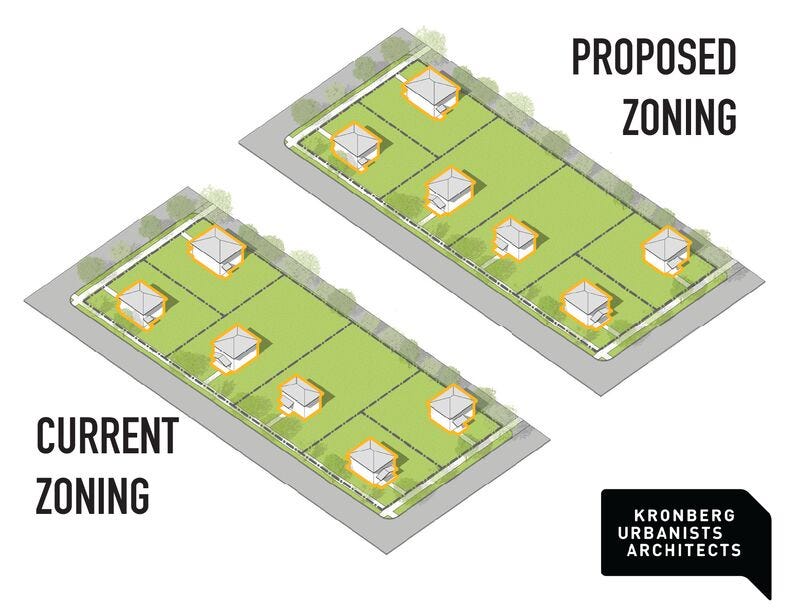

In this week’s post, we are going to unpack a graphic that showcases how minimum lot size regulations restrict housing opporunities.

VISUALIZING INCREMENTAL INFILL

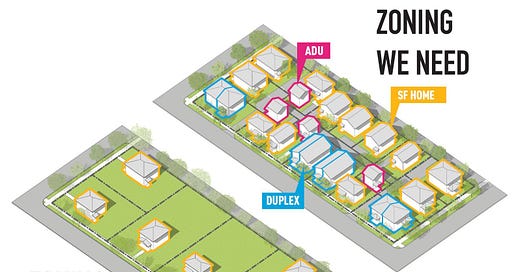

In the headline drawing of this post, Kronberg illustrates how incremental housing reforms can transform a single block into a more connected, livable community. The comparison focuses on a 1.5-acre block, showing two versions:

THE ZONING WE HAVE – a typical sprawling suburban block.

THE ZONING WE NEED – an incrementally densified alternative.

In THE ZONING WE HAVE, we see a typical land use pattern of any southern city, which yields six single-family homes. This pattern is characterized by large lots with large setbacks and large backyards. It’s a pretty standard suburban form across house size and wealth spectrums. An alley is present, but it appears to serve no purpose. Notice how much space is available.

In THE ZONING WE NEED, the same block face is infilled with a combination of small single-family homes (often referred to as “starter homes”), duplexes, and accessory dwellings (ADUs). The original alley is repurposed as road frontage, while a second alley, installed midblock, improves connectivity. The plan yields 24 homes—and that’s without any big apartments or much traditional missing middle.

Increasing density fourfold, all while retaining the neighborhood scale, is quite a feat.

HOW THE SAUSAGE IS MADE

These kinds of housing gains are happening more and more across the country, thanks to zoning reforms like reducing minimum lot sizes, eliminating single-family-only zoning, repealing parking requirements, and establishing ADU rights as inalienable. Together, these changes are yielding huge benefits.

Kronberg articulates multiple benefits of these reforms, which I’ve translated into a shorter list here:

Increased tax efficiency generates more revenue per acre and puts cities on stronger financial footing.

More sustainable infrastructure lowers the per-household cost of utilities, parks, sidewalks, and other public amenities.

Diverse transit options improve the viability of walking, biking, and public transportation.

Decreasing reliance on public subsidies allows citizens to put their money towards building the city’s housing stock instead of paying large corporations.

Expanding lower-priced housing lessens the supply strain in the booming South and serves the starter markets (e.g., first-time buyers and extended families) abandoned by traditional development.

Reducing sprawl and enhancing walkability strengthens neighborhoods and community ties.

Reinforcing localism ensures housing reflects local styles, built by and for the people who live there.

These benefits are huge—so why do cities keep getting in their own way instead of making changes that would lead to a more sustainable future?

Eric Kronberg is a great person to answer this question.

For a long time, he’s had a front-row seat to Atlanta’s messy politics, consistently showing up at public meetings to push for projects and reforms that make housing more affordable. He’s a go-to architect for many of Georgia’s nonprofits and land trusts, providing the plans that turn their policy charters into reality. His extensive writing on the subject cements his role as a leading voice in the fight for better housing. (I recommend these three books penned by their office).

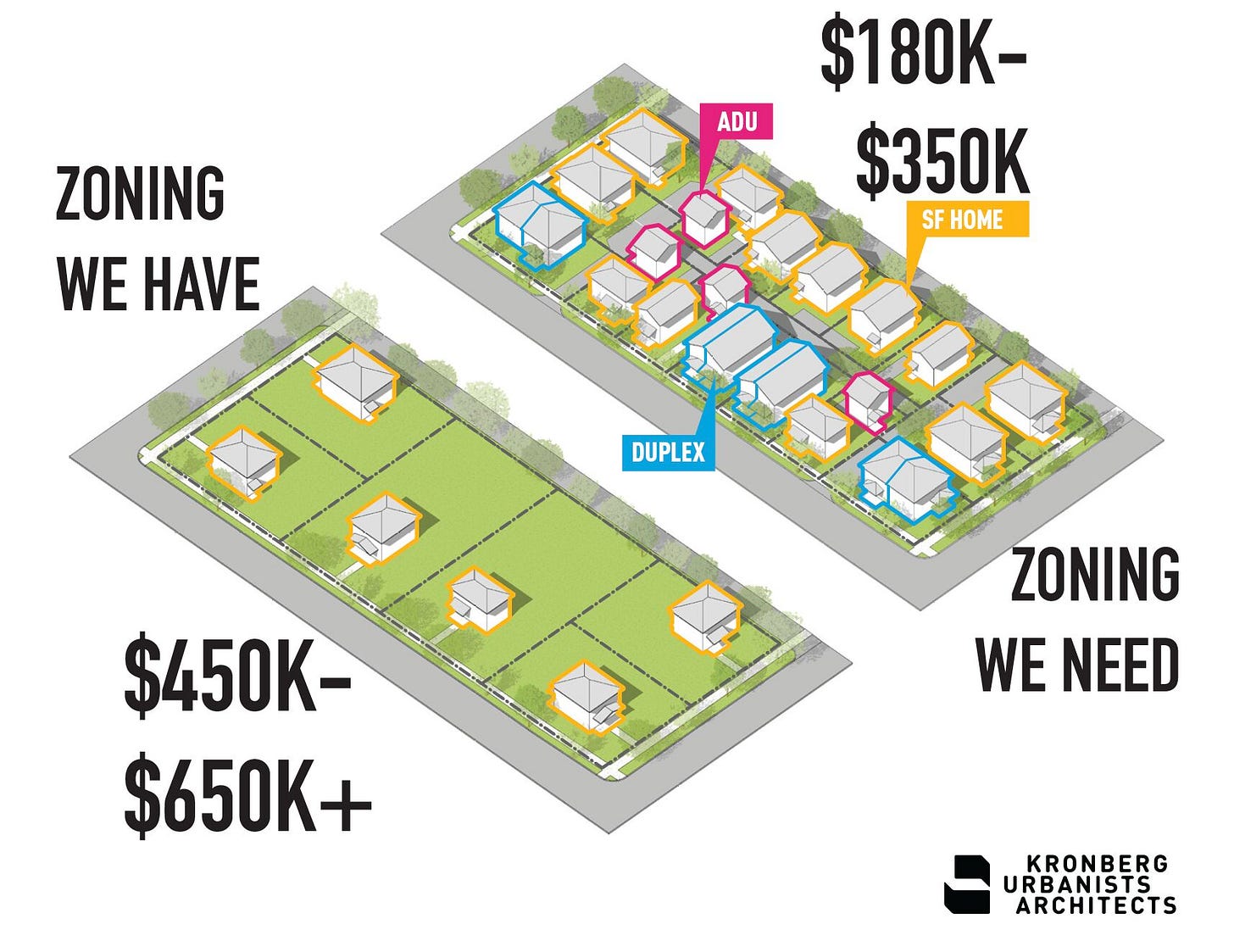

Kronberg is well versed in both Capital-A Affordable housing (state-subsidized and generally politicized development) and lowercase-a affordable housing (small-scale, non-politicized, incremental). Capital-A is a demand-side solution, while lowercase-a focuses on supply. Because of this, lowercase-a affordable housing depends almost entirely on zoning reform.

To emphasize the point that lowercase-a affordable housing is contingent on zoning reform, Kronberg added probable housing price info to the original graphic. This underscores how housing prices—ostensibly the #1 concern of many city governments now—can be substantially reduced with simple reforms.

There’s a longer presentation that walks through the math of this image, which I’ll cover in another post. But in short, it proves a clear mismatch between housing type and need: household sizes are shrinking, while new home sizes keep growing. Meanwhile, the market for small starter homes has collapsed, along with the supply of new homes in walkable neighborhoods. The result? A sustained downward pressure on affordability.

People are rightfully frustrated.

A small [but skilled] group of practitioners truly understands how to build housing more affordably—but they’re being blocked at every turn. Across the country, policies and regulations prevent them from doing their work, and their frustration is palpable.

In Atlanta, political inertia continues to handcuff property owners, stopping them from delivering lower-cost housing. Their exasperation is boiling over.

Kronberg puts it bluntly: “what if your city spent over $3M to rewrite zoning, all while 1) neglecting to demonstrably increase housing choices, 2) restricting housing options in accessory structures, and 3) imposing a draconian definition of family.” And why should we care about this scenario? “Because Atlanta.””

CONCLUSION

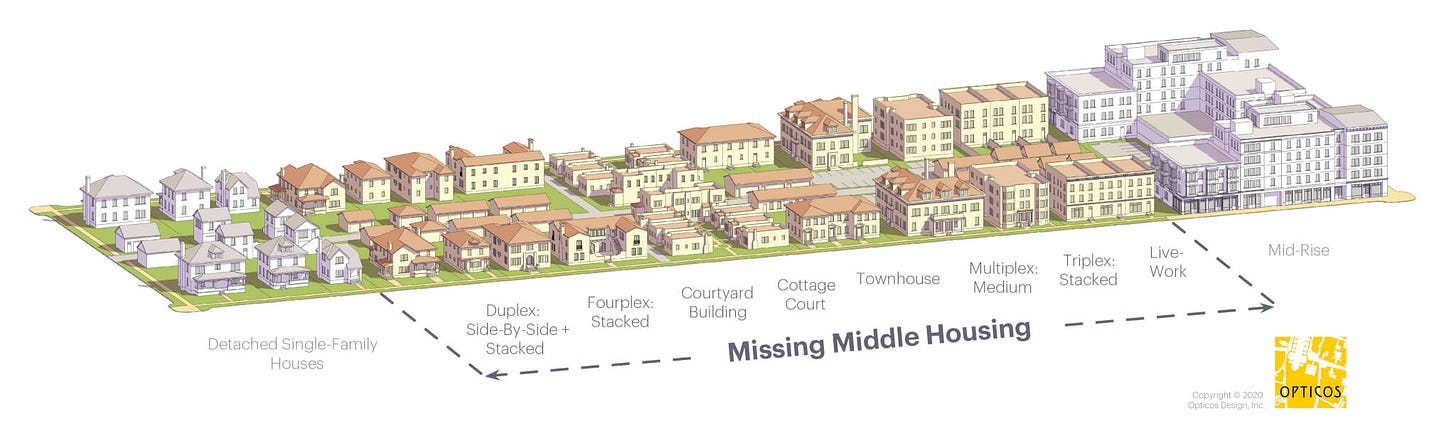

Real Estate Twitter (aka #ReTwit) Founding Father Sean Sweeney specializes in what I would call “Big Missing Middle,” while Eric Kronberg specializes in “Little Missing Middle.” Both are important to pay attention to because growth happens at the margins. It’s in these spaces that the right policy changes can truly transform cities and the lives of the people who live in them.

Kronberg’s work stands out because it’s scaled for the citizen developer—everyday people creating housing for their own communities. Historically, that’s exactly how most of our neighborhoods were built, and we’d all benefit from shifting back to that model.

He points to the city where I live, Durham NC, as a model to follow. Kronberg cites specific policies of ours as best-in-class:

reduce minimum lot sizes

allow duplex ADUs

permit fee-simple ADUs

remove limits on ADUs built on faith-owned property.

And he is right; Durham proves that strategic zoning changes make it possible to do something many cities struggle with: unlock more housing options without massive overhauls.

The most incremental zoning reforms include allowing ADUs, reducing minimum lot sizes, and permitting duplexes and lot splits by right. As Kronberg’s diagram illustrates, these small changes can transform a sparse, car-dependent city into a more walkable, connected community.

I have yet to see another way.

The fight for modest reforms will continue. Some cities will lead, others will follow, and many will resist affordability and access as long—and in as many ways—as they can. But for those who need housing and those who want to provide it, there are no workarounds; the only way is through.

That’s why I remain grateful for the work of folks like KronbergUA.

Thank you @erickronberg!