The 13 Crises of Architecture Schools

Why we must begin the total rebuild of the pedagogy

Next month, I have the privilege of being invited to participate in an event that brings together leaders from around the globe to ponder the future of urbanist education. The goal is to reconsider how we train students to build the places people love.

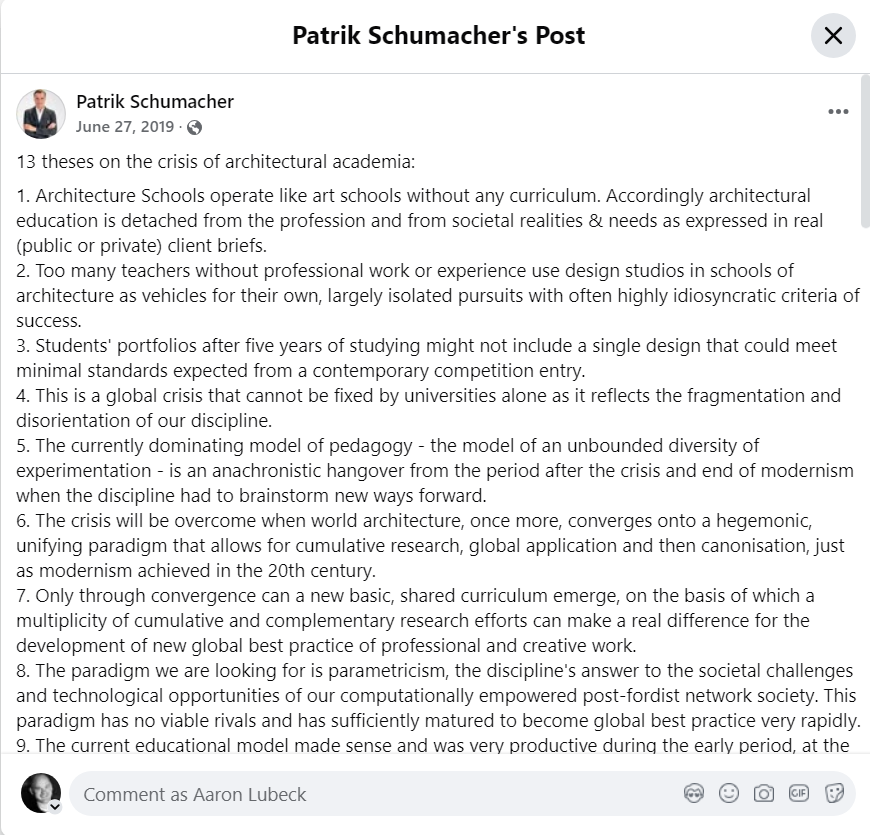

As part of the preparation, I was made aware of Patrik Schumacher, the principal and heir of London-based starchitect firm Zaha Hadid Architects, who penned a viral rant now known as “The 13 Theses on the Crisis of Architectural Academia”.

In it, Schumacher accuses modern design schools—their professors, specifically—of being self-promoting, disconnected from the real world, and ill-prepared to train the next generation of designers. And he concludes that all of this is leading to a crisis.

He is not wrong.

He made this scathing post on Facebook in 2019, and it made the rounds.

I agree with Schumacher on almost everything, though we probably diverge on what to do next. Schumacher nails the problem, perhaps as best as anyone ever has. After an examination of his arguments, which can be quickly validated by talking to folks who have recently attended these schools, it is clear that we can do better and need to do better.

Below is Schumacher’s complete list republished, with commentary through my typical lens of localism, incrementalism, traditional architecture and urbanism.

13 Theses on the Crisis of Architectural Academia

1. Architecture Schools operate like art schools without any curriculum. Accordingly, architectural education is detached from the profession and from societal realities & needs as expressed in real (public or private) client briefs.

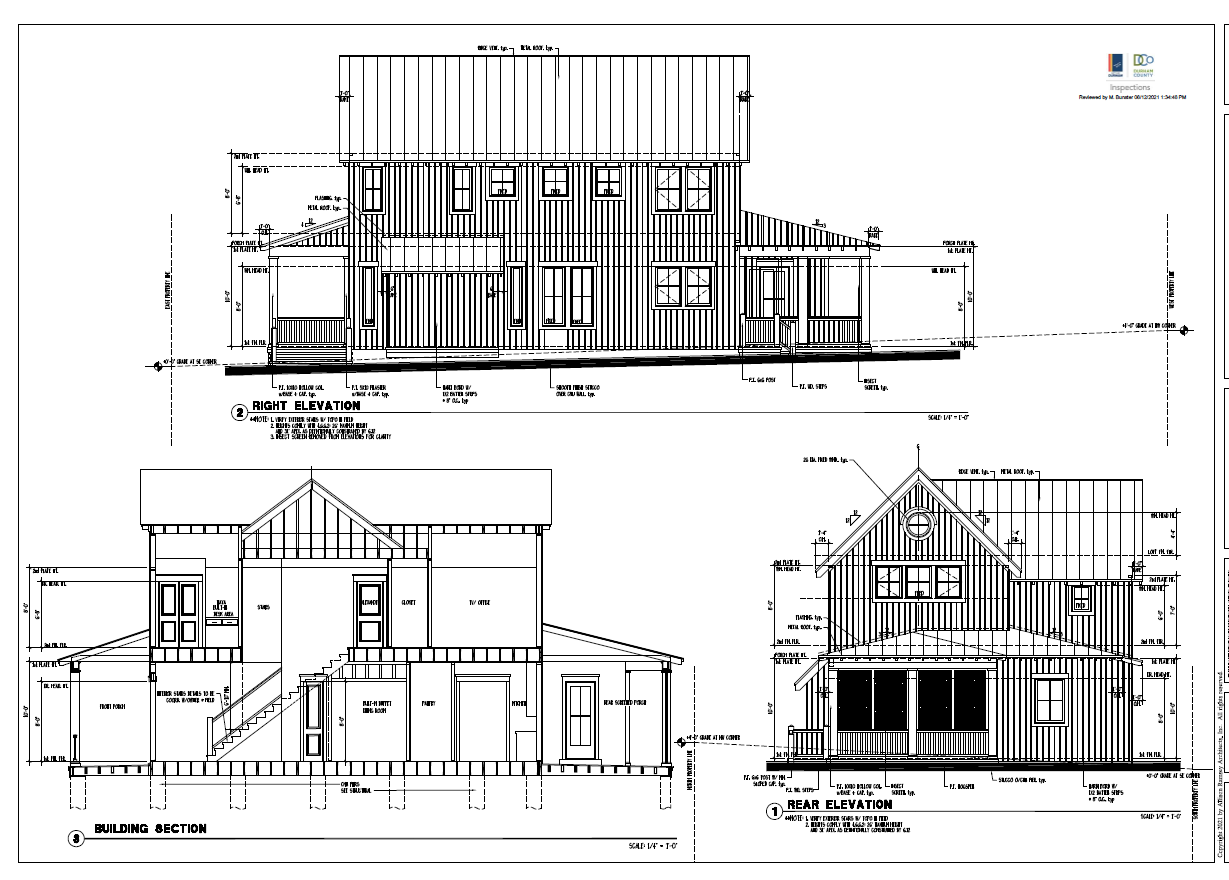

COMMENT: The same lack of practical curriculum can be said of many professional schools, but it is worse in architecture and planning. Also, I have learned with these two fields: the more prestigious the school, the less practical it is. New Urbanist Developer and friend Bob Chapman once told me, “The only thing Harvard GSD teaches you how to do is promote yourself.” Putting the long-running pissing match between new urbanists and GSD aside, I juxtapose this thesis with my experiences with Durham Technical Community College’s architecture programming, which my daughter started when she was 16. Durham Tech might be the least prestigious architectural program I could name, yet it presents students with everything they actually need to know (floor plans, elevations, traditional hand drawing), places the practical theory before the critical or conceptual. Groundwork and foundations matter. In schools, a new campaign to re-couple curriculum and reality is desperately needed. It is time to touch grass.

2. Too many teachers without professional work or experience use design studios in schools of architecture as vehicles for their own, largely isolated pursuits with often highly idiosyncratic criteria of success.

COMMENT: There is a broader problem in design and urbanism where less competent people (there are many) leverage public processes to force people to listen to them, often against their will. Clearly, it happens in academia, too. Too often, teachers focus on their needs over their students. And this is a problem, one which reeks of narcissism to me. Schumacher accuses design school teachers of “promoting their own agendas.” Why would they do this? Those who struggle to achieve desired respect in the competitive marketplace are naturally attracted to coercive mediums—often with captive audiences—to spread their seed. Who is more captive an audience than a student with a 4-year commitment contingent on making their teachers happy? (it’s actually 5 in stamp-granting architecture programs). This practice of validating the teacher at the expense of the student has to be eradicated. The focus of design training is training the pupil. Schools need to serve future architects, not failed ones.

3. Students' portfolios after five years of studying might not include a single design that could meet minimal standards expected from a contemporary competition entry.

COMMENT: Modernist Architecture Schools operate like governments, as they are about processes, NOT outcomes. Some schools do not care, apparently, if a student with a 5-year Master’s Degree cannot actually draft a submittable permit set. They care that students went through “the process,” were indoctrinated with “the values,” and had “the right thoughts.” That cannot happen. By the time kids graduate, they should have done permit sets—probably dozens of them. They should be prepared to pass professional exams, which schools also do not teach. The list goes on.

4. This is a global crisis that cannot be fixed by universities alone as it reflects the fragmentation and disorientation of our discipline.

COMMENT: Much like modernist American planning, which is also far down the woke spectrum and offers little hope of fixing itself, architecture schools appear to need outside help. It’s not clear how outside help would happen, but as Coby Lefkowitz noted in his excellent book Building Optimism, 90% of what schools are teaching, students don’t want. And 90% of the buildings people wish to see, schools don’t teach. What, then, can be done? Indeed, a professional mutiny would help, but that’s unlikely because a plurality of professional architects are products of this system. To blow it up would be to undermine their credentials and credibility. It’s asking lions to become dinosaurs. Change can come from legislatures, like the North Carolina Legislature’s perpetual meddling in UNC’s famously left-leaning agendas. But that’s messy, very much not in the spirit of the academy. It would be hard to imagine state senators stepping in to object to modernist architecture (modernism is linked to socialist expression, though few legislators are aware of it). But they might. The best option is competition. Each state should develop at least one architectural program committed to traditional training with traditional land planning and traditional buildings. Then, let the kids sort it out. Let them choose.

5. The currently dominating model of pedagogy - the model of an unbounded diversity of experimentation - is an anachronistic hangover from the period after the crisis and the end of modernism when the discipline had to brainstorm new ways forward.

COMMENT: The way I see it, we’ve lost our way and are adrift in the desert, searching for a unifying principle and North Star, where one is unlikely to be found. Perhaps such purposelessness (rootlessness?) is the byproduct of our obscene wealth. Some think that nihilism is linked to the decline of religion. Wherever we look, we find architecture that screams to us, “fuck it, nothing matters anymore.” Students in classes I teach cannot name a single building built this century that they would describe as “inspiring.” We need some grounding principles. It starts with leaders and ends with institutions. One person alone cannot change the course of a culture. It requires convening forces. The schools can be those convening forces; I have no idea who the leaders will be. Probably some pissed-off young people.

6. The crisis will be overcome when world architecture, once more, converges onto a hegemonic, unifying paradigm that allows for cumulative research, global application and then canonisation, just as modernism achieved in the 20th century.

COMMENT: Canons matter. While access to information is now limitless, a common body of knowledge is necessary. It’s how culture is made, defined, celebrated, and continued. What is that paradigm? What will it be? Schumacher’s canon is modernist, which is fine, though not universal. I suspect universal values might sound something like this: Cities matter. Design is humanizing. Traditions are to be honored, celebrated, and built upon. Local tastes must be studied and mastered. You can’t explore new until you understand old.

7. Only through convergence can a new basic, shared curriculum emerge, on the basis of which a multiplicity of cumulative and complementary research efforts can make a real difference for the development of new global best practice of professional and creative work.

COMMENT: It’s hard to come to common ground on a cannon. What would those books be? What would the foundation learnings of every architecture school offer? From there, each school can branch into its idiosyncratic curiosities.

8. The paradigm we are looking for is parametricism, the discipline's answer to the societal challenges and technological opportunities of our computationally empowered post-Fordist network society. This paradigm has no viable rivals and has sufficiently matured to become a global best practice very rapidly.

COMMENT: Parametricism uses advanced design tools to create infinitely adaptable, complex, and free-form spaces. I wrestle with this a little because so much of our bad architecture is trying to be all things to all people at all times. The results range from mixed to bad. In residential architecture, I like to design for a clear purpose. And if a room loses that purpose, it can change to another purpose. And even if the room isn’t perfect for the new purpose, that slight incongruency becomes part of the history, the story, and the charm. Pure efficiency is boring. The absolute pursuit of utility is how we get strip malls. This may be where Schumaker and I part ways. I get the need for flexibility, and I subscribe to that. But I think this is a thesis where things can go terribly wrong.

9. The current educational model made sense and was very productive during the early period, at the AA and Columbia, and indeed generated the ingredients of parametricism in the 1980s and incubated its development throughout the 1990s and early 2000s as the new viable way forward.

COMMENT: Things change. But professional architecture seems stuck in groupthink. It’s remarkable to me that architecture and planning—the fields that are ostensibly the most creative and problem-solving—are, in practice, extraordinarily ideological, monolithic, and unchanging. Someone will break this, eventually, and I suspect it will be easier than people think. The impractical, overly intellectual post-modern values of both professions are frail: when pushed, they’ll collapse like a deck of cards.

Architecture School cannot be Art School. The difference between architecture and art is utility.

10. Integrated, cumulative research and design took place and started to interface with practice. However, in contrast to the successful Bauhaus transformation during the 1920s, the necessary institutional transformation away from the art school model to a science school model did not take place.

COMMENT: In what I’m about to say, I run the risk of sounding like I’m essentializing Art vs. Architecture as “something to simply look at” vs. “something that serves a purpose.” That is not a dichotomy that holds. Art has a purpose and architecture can be beautiful. But what I’m trying to underscore is that utility (as opposed to a larger ideological sense of purpose) is absolutely, inarguably central to architecture.

It follows, then, that Architecture School cannot be Art School. The difference between architecture and art is utility. The former implies use. It implies human interaction. It is a criminal disservice to treat students as artists, exclusively, and not teach them how to serve their clients. Clients will ultimately need them to do practical and executable construction plans for the built environment, not create statements via art.

11. There are cycles of innovation. Creative work, research, and discourse culture, including teaching patterns and personalities, in the middle of the cycle should be very different from the beginning of a new cycle. We are no longer in the infant phase of the new paradigm. Accordingly, our culture and role models have to adapt. The AA school culture can initiate but not commit to, advance, and work through a paradigm. The problem is that the seminal role the AA played in the eighties and nineties triggered the worldwide imitation of its culture at a time when these ways of working were getting in the way of further progress.

COMMENT: I do not know enough about the Architectural Association (AA), which the German author references here. The main point seems to be that adaptation is perpetual. The only thing constant is change, and when you are stuck within a system, and vested in that system, you are naturally resistant to change. But such resistance is suicidal because you’ll lose touch with the world, specifically those you serve, which ultimately yields the end you were seeking to avoid—death through irrelevancy.

12. The lack of political adaptation to post-Fordism got in the way too: the 2008 financial crisis, the political regression and economic stagnation since have so far prevented the hegemony of parametricism just as the 1929 crisis, fascism and WW2 had retarded modernism.

COMMENT: Fordism refers to the Henry Ford assembly line: predictable and repeatable industrialism. Schumaker suggests that his parametricism—the managed complexity that modern architects orchestrate--is off schedule from the dysfunctional politics of the time. Again, I am not sold on parametricism. Still, I do agree that messy, bottom-of-the-barrel and often-valueless politics do not help form a helpful common core of beliefs that society’s designers can act upon. Post-modernism, some might call it late-capitalism shit, is the result.

13. The political frieze on urban density, programmatic mixity and typological innovation blocks the competitive advantages of parametricism and retards its advance. These background conditions obscure the historical mal-adaptation of our discipline and of it’s teaching culture.

COMMENT: Schumacher offered up a wonky way of saying it, but essentially: zoning sucks, placeless land planning sucks, and placeless architecture sucks. Schumacher blames politics, I blame planning (which I believe leads politics in creating bad rule-making). This freeze (Frieze must mean something different in Deutch?) does prevent us from a better future, which is widely accepted by anyone seeking to positively participate in American land use discourse.

CONCLUSION

While we can all agree that our buildings, land plans, and schools are not where they should be, we don’t seem to be able to agree on what to do about it.

Truth be told, I am not a huge fan of Schumaker’s design work. In Patrik’s defense, I like very little modernism, and I am confident he would not care what I think anyway— but I respect that other people appreciate his work. His architecture is pretty irrelevant to the societal point of his Facebook post. I do believe he is spot-on with his critique of the pedagogy: our schools just ain’t cutting it.

In my reform advocacy work, the approach is pretty simple. Like an oncological surgeon, it’s important to identify in advance how far back the cancer is. First, you deal with it in non-invasive ways. Then eventually—and this is sadly common when coping with non-responsive governments—you have to reach deep to grab all the roots of the disease. When the sickness is deep, the solution will be invasive. Sometimes the target is code, sometimes it’s politics. As Shumaker points out, sometimes it’s the schools. In the case of architecture and its twin sister, planning, the schools are a mess. That’s the real problem. That’s the origin of so many problems.

Our built environment is downstream of our architecture schools. They are manufacturing poop and putting it in the river.

If we are to prepare for the 2030s, which I maintain will be the best decade for American townbuilding in a century, it’s high time to set the academy straight.

In my opinion, a total rebuild is in order.

What I read with his list is a desire to return to a universal modernism, like the CIAM days. And that it’s tied to the same political leanings (Marxist).

Many of his observations are true, but the cure can be worse than the disease.

The problem in architectural design grew hand in hand with the professionalization of all of architecture and building, and the parallel administrative state that oversees it all. It would seem if we want to really change things, those are the places to look. For example, allow vastly more types of buildings to be designed by non-licensed architects. Allow self-certification of projects. Deregulate zoning.

Let the change come from the masses, not the academy (which obviously doesn’t want to change)