Some Thoughts on the Democratization of Land Use (aka zoning)*

I'On's Geoff Graham explains why the politicization of housing leads to more sprawl and less affordability.

The biggest issue with housing discourse is that cities' words don't match their actions, particularly when it comes to comprehensive plans and zoning.

This disconnect—cities saying one thing and doing the opposite—is all too common in development discussions. It consistently obstructs the creation of the walkable, vibrant future many of us want.

Geoff Graham, a developer involved with I’On, recently tweeted how political pressures forced them to build something different than what they originally planned. As he explains, this outcome harmed the development, the town, and the lower-wealth people they sought to serve.

His full account is below, following my thoughts on why comprehensive plans and the politicization of housing (zoning) are fatally problematic. These documents not only fail to serve their intended purpose, but often do the exact opposite.

THE BROKENNESS OF COMP PLANS (and ZONING)

The utility of comprehensive plans (comp plans) is questionable. These plans are supposed to represent the community’s vision, but in reality, they are little more than formless value statements shaped by current political trends. To put this in context, election cycles rarely exceed 24 months. I’On took about 30 years to build.

For Geoff Graham, the political climate didn’t align with the comp plan, forcing the removal of the more affordable multifamily housing as a prerequisite to securing approval for the project.

Lower-cost housing is often blocked by politics, but it is usually developers who get blamed. Policy creates a housing shortage, and then politicians shift the blame onto developers. It’s a classic deflection of responsibility, now ubiquitous in American housing politics.

In my view, American cities would be better off without comp plans. They’ve become just another procedural barrier to progress. Comp plans are particularly obstructionary to anyone seeking non-uniform developments, which walkable mixed-use communities (like I’On) inherently are.

Every city suffers from this problem, which presents as politicians acting in ways that are in direct defiance of their comp plans. That’s exactly what happened at I’on.

HOW POLITICS MADE I’ON WORSE

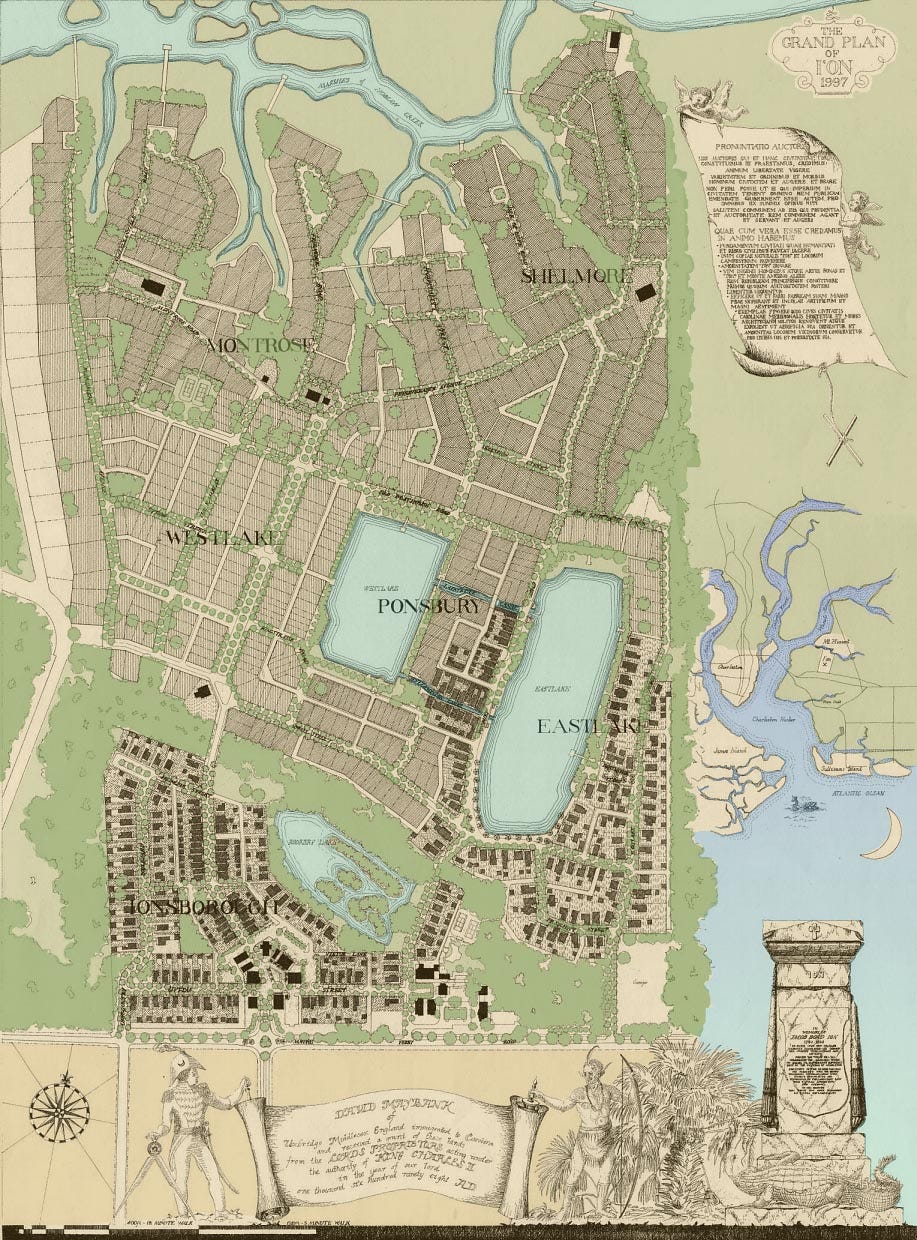

Located in Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina, just north of Charleston, I’On is a well-designed, new urban development with top-notch land planning, architecture, and mixed uses. However, it lacks lower-cost housing, a critical societal issue.

Why isn't there any lower-cost housing?

The town’s comprehensive plan at the time of entitlement supported a vision of walkability, mixed-use spaces, and diverse housing types. But politically influenced zoning laws required a campaign to turn this vision into reality.

The rezoning process was costly and contentious. The developer had to make significant compromises, including eliminating multifamily housing and most commercial space.

The result, though an improvement over previous zoning, still led to Mt. Pleasant continuing its habit of underwriting sprawling, car-dependent growth. At the edge of the city, large-scale retail replaced local businesses. The disconnect between housing, commercial spaces, and infrastructure continued the harmful effects of zoning.

My conclusion? The politicization of zoning prevents better housing. Bad zoning politicizes everything. Therefore, zoning is the problem.

Read on for Geoff’s first-person account, as he explains it better than I can.

Some thoughts on the democratization of land use (aka zoning),

how it impacts communities, how it promotes distant and financialized interests, and why it is evil

by Geoff Graham

To satisfy the political requirements imposed by zoning we had to eliminate all multifamily and the majority of our commercial to secure the entitlements we needed.

- Geoff Graham

When we sought our rezoning for I'On, the town's staff was an important advocate. They had just completed a large comprehensive plan calling for exactly what we wanted to build (walkability, mixed-use, diversity of housing types, infill, etc), and had effectively been recruiting developers who shared that vision. Unfortunately, the town's zoning did not reflect their plan and so anything a developer wanted to do that aligned with vision still required a political campaign.

Fortunately for us, a number of influential local groups supported the vision laid out in their comprehensive plan, and when we began seeking our rezoning, they allied with us to help us secure the permissions we needed to build something special. The Coastal Conservation League was among them and their assistance was crucial. What we did for three years would appropriately be called "beating the drum." I would guess that at the time there had never been more community outreach for any endeavor in the town's history.

It was expensive and, unfortunately, divisive. Zoning is divisive by its very nature, so the acrimony was unavoidable. It imposed costs that were direct and indirect, obvious and hidden. Those costs were ultimately shared both by us (the developer) and the community.

In the end, we had more people speak against our project than any other proposed development in the history of the town (twice, because we were shot down in our first rezoning attempt). We also were the first to have more people speak in favor of a development than against.

Nevertheless, to satisfy the political requirements imposed by zoning (which elevate the interests of the most outspoken opponents over of the interests of the property owner or the long term best interests of the community), we had to eliminate all multifamily and the majority of our commercial to secure the entitlements we needed to build on our undeveloped 244-acre infill property in the heart of one of the fastest growing towns in the southeast.

In the end, the town council decided to push new multifamily to the outskirts of town where they had no infrastructure and the tomatoes and strawberries would not object. Additionally, rather than having lots of smaller-scale (and locally-owned) commercial nearby, they preferred to have large-scale big box retailers out on the edges of town. I recall some of these people actually invoking the donut to describe their land use vision.

Predictably, the net effect of the donut strategy has been that all these people now make lengthy car trips through town on ever-widening arterials. They mayn't walk or bike around, nor may they make considerably shorter trips by car (or golf cart) via a network of streets that diffuses traffic. The housing in which they live is built and owned by the nation's largest builders and REITs, the number of small local retailers is negligible, and most of life's necessities are purchased from giant financialized corporations that reside in ugly boxes accessible only via cars and highways.

Moreover, employers must pay those without the means to afford luxury to drive great distances to work in the stores, in the schools, on the jobsites, etc—which of course, makes everything more expensive. That cost has climbed so much that building and maintaining robots to prepare a meal or make a coffee is becoming more cost-effective than paying someone to do the same thing after driving an hour to and from the workplace.

This is what the democratization of land use (aka zoning) hath wrought.

Empowering people to have control over things they don't own is evil and has terrible results.

To be clear, I am a huge fan of input from the community. Developers (like creators of any good or service) want to create things that people want. However, empowering people to have control over things they don't own is evil and has terrible results—our built environment being among the more obvious.

Of course, developers should shoulder the external costs associated their project and never should the cost of their critical infrastructure be socialized (as is the case in exurban development), but in general, the right way for things to be is for interested community members to seek to persuade the developer, rather than the other way around.

Nowadays, people think I'On is amazing, and it is obviously way better than what the prior zoning allowed, but it is far from what it could have been without zoning and there is no amount of additional drum beating that would have gotten us there. We did the best one could do under the constraints of the day.

Geoff Graham is an Atlanta-based entrepreneur with deep experience in real estate development and software. His most significant prior ventures include the development of I’On, a mixed-use, 762 homesite community in Mount Pleasant, SC (1997 to present), and GuildQuality, a software-as-a-service business serving the residential construction industry (2002 to 2019).

During the first five years of I’On’s development, Geoff managed the neighborhood’s vertical and horizontal construction, recruited the builders and managed the building program, and was instrumental in the creation and administration of the neighborhood’s design guidelines. Since the completion of the first homes in 1998, I’On has earned accolades for its financial success, its exceptional design, and its environmental sustainability. I’On and its homes have been widely featured in both consumer publications and professional journals.

So, there's a property line 40 feet from the back door and the parcel on the other side is not that well-suited for more residential (we, the neighbors, are modest townhomes in a mixed-use area), but it would be "evil" for me to object any number of noxious uses that might be proposed 40 feet away because I don't own it? I think not. Kicking folks out of the process, or trying to, I guess, will just create more NIMBYs, not fewer.

In looking at your work, which seems great, I understand your frustration and hope that's leading you to overstate the case against people being involved in issues that affect them. And my thought for you, as someone who has been responsible for some successful zoning reform and slashing the processing time for big projects around here roughly in half (then the guy I hired to replace me, cut it even more, though that took a decade) is to re-think your position on comp plans. The way we got where we are, with reduced processing times and a successful walkable growth center, was by doing a new plan (since replaced by a better one) that set not just the tone, but enough details in place, that the zoning had to be redone to match. That may be harder in SC than here, and you're probably also thinking its not the developer's job. But its a lot easier to talk about what needs to change in general and get that in place, than it is to talk about it in the formal review of a project.