Durham's First Duplex ADU

Recent reforms are unlocking new methods of affordability, all with zero public subsidy.

Accessory Dwellings are small houses that are subservient to primary dwellings and often placed in backyards. They are colloquially known as granny flats, mother-in-law suites, or simply “ADUs.” Across the country, ADUs are fast becoming a large part of the housing solution because they are generally citizen-developed, skirt toxic housing politics, and require no public subsidy.

My hometown of Durham is a leader in the form.

In Durham, ADUs are regulated by section 5.4.2 of the Durham Unified Development Ordinance (UDO), which articulates several entitlement rights:

ADUs are allowed by right on single-family and duplex lots.

No additional parking is required.

The heated floor area of the ADU shall not exceed 1,000 square feet on a single story and 1,200 square feet total.

The maximum height of an accessory structure shall not exceed the greater of a) two stories and 32 feet or b) the height of the primary structure in feet.

While these standards are permissive relative to most American cities, the most important clause was added as part of the city’s 2023 reforms. It allows for Duplex ADUs, one of the first cities in the country to do so. It reads:

If a primary dwelling is a single‐family residence, an accessory structure may be a duplex, so long as the total heated sf of the Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU) does not exceed 1,200 square feet for both units combined.

The logic was pretty simple. A growing number of citizens wish to build housing for their community, and 2019 reforms (known as Expanding Housing Choices) allowed each lot to build a duplex plus an ADU—three homes on residential lots. But, a problem arose because many prospective citizen homebuilders wished to build housing but did not wish to duplex their primary home (often for build code complexities or privacy reasons).

Since three homes were already allowed on a lot by the 2019 reforms, the more recent 2023 reform allowed two of those three homes to be located in an accessory structure. It didn’t allow for more housing on the lot; it only allowed for a more viable allocation of those homes. This added flexibility enhances citizen choice, resulting in variability customized to the unique needs of the lot, owner, and community.

Durham can now see beautiful homes like the Washington Duplex (recent winner of the or Urban Guild’s Missing Middle Merit Award), which is now allowed by right.

CONTRARY TO OPINION, ADUs DO MATTER

In housing discourse, a group of naysayers is always on standby to scoff at any attempt to reform zoning or create additional housing. They are particularly vitriolic toward incremental reforms, which ADU reform clearly is.

In Durham, the typical retort was that “ADUs are too small to matter.” Oddly, this was presented as a reason to oppose the reform, even though their ostensible argument was that the growth of ADUs would be too small in number to rise to the level where it would be worthy of objection. Sadly, such hyperbolic contradictions are now the new normal for NIMBY arguments in central North Carolina.

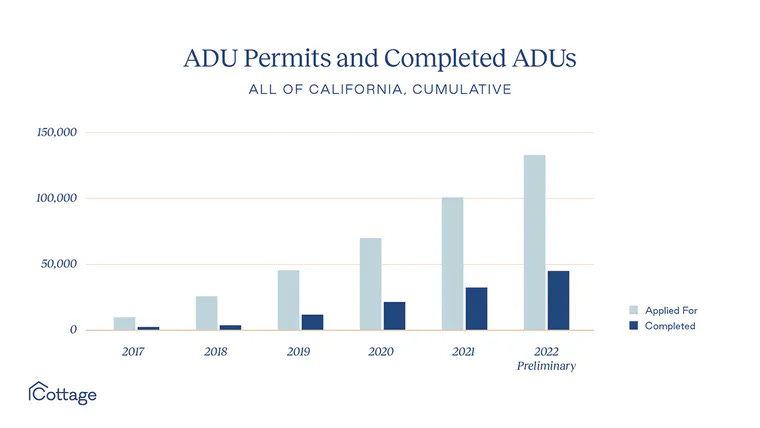

In any case, California is proving this thesis untrue. ADUs do matter. According to Cottage ADU’s Impact Report, 1 in 7 homes built in California in 2021 was an ADU. According to CaliforniaYIMBY’s Nolan Gray, since 2017, Los Angeles has permitted nearly 35,000 accessory dwelling units—homes that were largely illegal prior to state intervention.

All of this is the result of an ambitious statewide SB 13 Bill that made ADUs legal statewide, overriding the local Californian NIMBY obstruction campaigns that had long banned them. Similar legislation passed the North Carolina House in 2023 (HB409), penned by Durham’s Vernetta Alston, but was never heard in the Senate.

Reforms at state and local levels are essential. Contrary to the narrative some anti-housing advocates are now trying to establish, the state does not “do zoning.” Mostly, states have nothing to do with local zoning, but they do, from time to time, restrict local governments from stripping certain property rights that might be viewed as natural and inalienable. Today, because so many property rights are over-encumbered by a century of overzealous central planning, state legislatures are re-establishing those rights by handcuffing cities.

Statewide ADU reform is precisely such a restriction. Legislatures are punishing cities for decades of bad behavior—anti-citizen behavior, anti-consumer behavior, anti-choice behavior.

FOSTERING THE MOST LOCAL OF LOCALISM

The primary playing field for incremental housing is now in the backyards of non-professional citizen builders, who are starting to build small homes across the country.

In the Duplex ADU photographed here, the square footage is spread evenly over two floors, with two identical 500sf 1-bedroom apartments. Each is given a generous private porch, critical in the Southern climate.

The porches also create semi-private space, which is key to living well in densified areas. “Semi-private” means that it faces the public realm and would not be completely sealed off from others’ spaces, but it is designed to be exclusively used for the tenant, so they can feel free to furnish it and use it how they please. This indoor-outdoor play is needed to live well in small spaces. In this case, both duplex units overlook a large fenced backyard.

My opinion is that it is gorgeous and will create unprecedented new access for students, young people, and the working class to live in a relatively wealthy neighborhood close to downtown. Win and win.

DUPLEX RIGHTS MATTER

This project would not have been viable if not for Durham’s 2023 reforms. Prior to that, only single-family duplexes could be built, which carry a higher cost per unit burden, making them less financially viable to build. Inevidibly, as that threshold lowers, more projects pencil, and more projects get built. And projects become more affordable as they are built.

The math on new construction for-rent products is ruthless right now. It’s hard to get anything to work. Where things do work, they are typically small, multiple units per fixed-cost lot, with simplified architecture (often rectangular to maximize footprint and minimize costs).

They also usually require some combination of free or cheap land (such as an already existing backyard), good location with high demand (most of urban Durham would quality), and/or free or cheap debt (which continues to be a problem because ADUs are hard to finance, which I will flush out in a separate post).

Small duplexes are great examples of what Chuck Marohn of Strong Towns calls “The Next Increment Up.” When districts become unaffordable, they should, in principle, rezone to The Next Increment Up—essentially what Durham did. This allows for incremental change, protecting historic fabric while not undermining universal principles of equity, access, and opportunity.

In short, if your whole neighborhood is single-family homes, you don’t want it to be rezoned for skyscrapers or Texas donuts. But duplexes should be OK. Most look and scale consistently with the original fabric.

Duplex ADUs are even better. ADUs, generally, are in the backyard. It’s the perfect place to experiment and even do wacky things.

People who know me know that I loathe modernism, but if you are going to do something weird, wacky, and different from the rest of the neighborhood, it's undoubtedly less disruptive to do it in your backyard than in the front.

ADUs are the least invasive tool for adding density. In this case, the homeowners, both nurses, are providing affordable housing, increasing the flexibility of their family's visits, providing choices in the community, and increasing the tax base—all with zero public subsidy. They are also tripling the density of the lot without affecting the historic streetscape at all.

CONCLUSION

There are no silver bullets in housing or affordable housing, but there are some universal truths. Citizen builders are the way. They have always been the way. It’s not lost on me that until recently, all of the truly lower-cost homes in Durham (and across the globe) had been built by local hands with local money. This method is scalable, organic, unique, local, historically accurate, and, most importantly, requires neither subsidy nor the politics inherent in larger projects.

Imagine what your city would look like with thousands of these ADUs.

Would it be more affordable?

Would it be more interesting to have thousands of locally owned small homes?

Would it be more equitable for people of lower wealth to access the amenities of wealthier neighborhoods?

This is the way. I applaud the work and look forward to seeing more of it.

If Durham is like most American cities, probably 3/4 of the residential lots are single family homes. Another word for that is scale. As in, that’s how you scale change. Make it accessible to the masses, make it simple and easy, and nature takes its course. Love the duplex ADU idea.

Here in my city, we had to do rental compromise for our ADU ordinance. That is, the ordinance requires one of the structures be owner-occupied. Do you have such issues, and/or short-term rental concerns?